The African Development Fund is preparing for a new funding round aimed at sustaining development efforts across some of the continent’s most vulnerable economies. The Fund, which serves as the concessional financing arm of the African Development Bank Group, supports 37 low-income African countries, many of them affected by conflict, institutional fragility, or long-term economic disruption.

Since it was established more than five decades ago, the Fund has channelled over $45bn into grants, guarantees, low-interest loans, and technical assistance. These resources have underpinned infrastructure projects, social programmes, and institutional reforms in countries that would otherwise struggle to access affordable financing.

Every three years, donor governments and partners convene to decide how much capital the Fund will have available for the next cycle. The upcoming replenishment, the seventeenth in the Fund’s history, will cover the 2026–2028 period and is scheduled to be finalised in London later this year. While the previous round raised a record $8.9bn, the outlook this time is more restrained as development budgets tighten across many donor countries.

Despite those constraints, advocates are pushing for a far more ambitious target of $25bn. They argue that scaling back support now would jeopardise fragile gains made in recent years and could increase instability well beyond Africa’s borders.

UK development minister Jenny Chapman framed the replenishment as a test of international resolve, describing it as a chance to reaffirm long-term commitments to African institutions while also modernising the way development finance is delivered in an increasingly complex global environment.

Sidi Ould Tah echoed that view, portraying the Fund not as a cost but as a shared investment. Over the past decade alone, he noted, ADF-backed projects have expanded electricity access to more than 18 million people, boosted agricultural output for millions of farmers, improved water and sanitation services for tens of millions, and supported transport links serving nearly 90 million people.

Somalia’s Debt Relief Marks a Turning Point

One of the clearest examples of the Fund’s impact can be seen in Somalia, where economic conditions have begun to stabilise following comprehensive debt relief earlier this month. The African Development Bank cancelled all outstanding loans owed to the Fund over the 2024–2039 period, reducing Somalia’s external obligations by nearly $18m and freeing up scarce public funds for development needs.

The decision followed Somalia’s completion of the Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative in late 2023. The programme, overseen by international financial institutions, sets out a demanding reform path for heavily indebted nations, tying debt cancellation to progress on governance, revenue mobilisation, and social investment.

Completion of the initiative unlocked full relief from multiple multilateral creditors. Once fully applied, Somalia’s external debt stock will fall dramatically—from more than $5bn in 2018 to under $600m—giving the government space to redirect resources towards rebuilding basic services and state capacity.

Reconstructing a State From the Ground Up

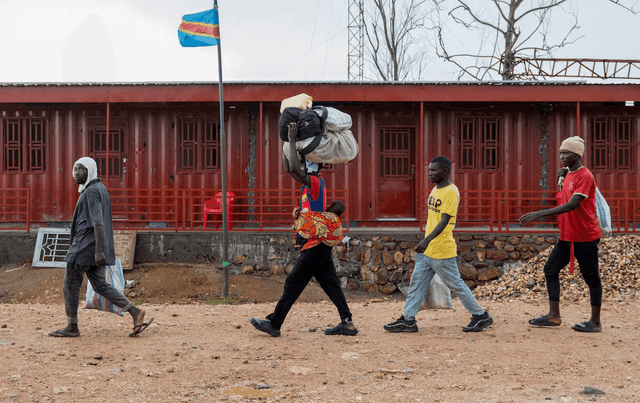

Somalia’s debt crisis was compounded by decades of conflict. Between 1991 and 2012, the country lacked a functioning, internationally recognised central government. During that period, financial records were lost, arrears accumulated, and relationships with creditors deteriorated.

Following the formation of a federal government in 2012, restoring basic economic governance became an urgent priority. The African Development Bank, using resources from the Fund, provided grants and technical assistance to help reconstruct Somalia’s debt records, establish a Debt Management Unit within the Ministry of Finance, and design strategies for arrears clearance and engagement with international lenders.

Mohamed Sadaq, who later led the unit, described the process as foundational rather than incremental. With support from AfDB experts, Somalia rebuilt its external debt database from scratch and gradually normalised relations with creditors. By the mid-2010s, the country had a functioning debt management system staffed with trained officials—an essential prerequisite for accessing concessional financing.

The Fund contributed $3.5m to set up the unit and an additional $7.59m between 2017 and 2023 to strengthen macroeconomic oversight, transparency, and accountability in public finances.

Even so, development partners caution that progress in fragile states is rarely linear. Without sustained support, institutional capacity can quickly erode, reversing hard-won gains.

Looking Beyond Traditional Donor Funding

As global aid budgets come under increasing strain, attention is shifting to how the Fund can stretch its resources further. The next phase of financing is expected to place greater emphasis on mobilising private capital alongside concessional funding.

According to Valerie Dabady, who oversees resource mobilisation and partnerships at the African Development Bank, one option under consideration would allow the Fund to raise money directly from capital markets. Doing so would require changes to its founding charter but could significantly expand its financial firepower.

The proposed “Market Borrowing Option” would enable the Fund to issue debt, potentially generating up to $5bn in additional resources every three years. Support for the idea is growing, although formal approval would require backing from at least three-quarters of shareholders.

Proponents argue that without such innovations, the Fund risks being constrained by donor fatigue at precisely the moment when demand for concessional finance is rising. For countries emerging from conflict or debt distress, they warn, the cost of hesitation could be far higher than the price of continued support.