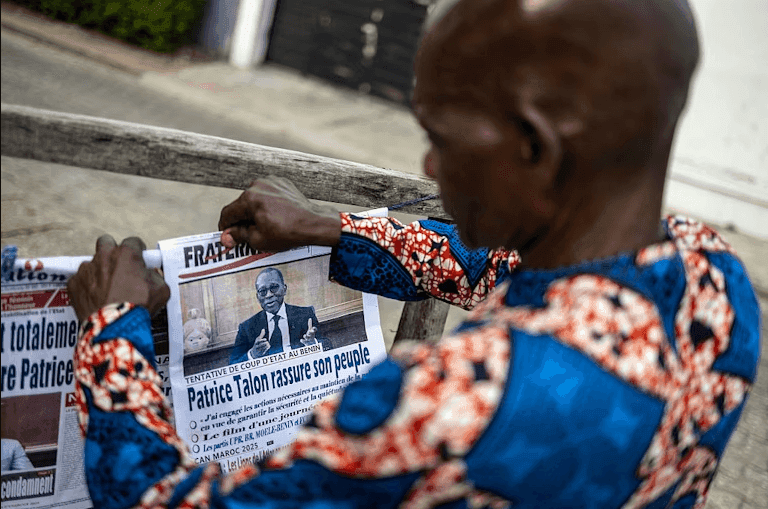

In early December 2025, a group of military officers attempted to overthrow the government of Benin. Unlike the wave of coups that have swept across the Sahel and parts of West Africa since 2020, this takeover bid did not succeed. One key reason was the unusually swift military reaction from Benin’s regional partners.

Benin, a West African country with a population of roughly 14.8 million, shares borders with Togo, Burkina Faso, Niger and Nigeria. Following urgent appeals from President Patrice Talon’s administration, Nigeria scrambled fighter jets, while the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) activated elements of its standby force. Their mission was clear: neutralise the mutinous units and restore constitutional order.

This external intervention proved decisive. Although the coup plotters achieved some early gains — including seizing the national broadcaster, occupying a military base and briefly detaining the two highest-ranking officers in the army — the momentum evaporated once Ecowas forces entered the picture. Officers who might have wavered quickly concluded that the loyalist side would prevail. In the end, the uprising failed to trigger wider support. Fourteen individuals were arrested, while a small number of suspects remain at large.

As a researcher who curates the Colpus database on coups and studies post–World War II seizure-of-power attempts, I have closely tracked Africa’s post-2020 surge in military takeovers, now entering its fifth year. Although many details surrounding the Benin plot — reportedly led by Lieutenant Colonel Pascal Tigri — remain unclear, three broader structural conditions help explain why such an attempt emerged.

These include: the steady erosion of democratic checks under Talon since 2016; a sharp deterioration in security in northern Benin linked to jihadist spillover from the Sahel; and the growing “contagion effect” of coups radiating westward from Africa’s coup belt.

From Democratic Model to Democratic Strain

Benin has not been known for recent military takeovers. Its last genuine coup attempt dates back to January 1975. Yet earlier history tells a different story. Between independence from France in 1960 and the mid-1970s, then-Dahomey experienced nine coup attempts, making it one of the most unstable states in sub-Saharan Africa during the Cold War.

That cycle of instability ended with the long personalist rule of Mathieu Kérékou (1972–1990), followed by a transition to electoral democracy after the Cold War. For years, Benin stood out as a rare democratic success in a difficult regional environment. Living standards improved gradually, and economic performance remained strong — growth reached 7.5% in 2025. The unrest of late 2025 cannot be attributed to economic collapse or mass impoverishment.

However, democratic indicators tell a more troubling story. While elections have continued, limits on executive power have steadily weakened since Talon took office. Data from scholars Barbara Geddes, Joe Wright and Erica Frantz, alongside assessments from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project, indicate that Benin slid back into the category of electoral autocracy in 2019.

That shift coincided with parliamentary elections in which opposition candidates were barred, widespread protests were suppressed, and internet access was cut. Two years later, an opposition boycott paved the way for Talon’s uncontested re-election.

Although V-Dem data show modest improvements since 2022 — including opposition participation in the January 2023 legislative elections and Talon’s pledge not to seek a third term — political tensions have persisted. In late 2024, the government claimed to have foiled a separate coup plot involving a potential 2026 presidential contender. More recently, parliament’s decision to establish a Senate was denounced by opposition figures as a mechanism for Talon to retain influence after leaving office.

With the main opposition party excluded from next year’s presidential race, Talon is widely expected to transfer power to his close ally, Finance Minister Romuald Wadagni. Against this backdrop, Tigri framed his actions as an attempt to liberate the population from what he described as authoritarian rule — and likely aimed to derail the upcoming 2026 elections.

Escalating Insecurity in the North

Security failures featured prominently in the coup leaders’ justification. They accused the government of neglecting worsening violence in northern Benin and failing to adequately support soldiers killed in combat.

This pattern mirrors developments elsewhere in the region. In Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, rising jihadist violence preceded military takeovers. Since 2022, insurgent activity has increasingly spilled southward from the Sahel into coastal West Africa. Benin’s northern regions have not been spared.

Conflict data from ACLED reveal a sharp increase in political violence since 2022, with fatalities peaking in 2024. Much of this escalation is linked to the expansion of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), an al-Qaida-affiliated group that has broadened its operational footprint. Notably, JNIM carried out its first deadly attack inside Nigeria in late October.

While Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have aligned themselves with Russia through a 2023 defence pact — the Sahel Alliance — Benin has taken a different path. It continues to cooperate closely with Western partners, including France, which has expanded military assistance since 2022. In September, the head of US Africa Command visited Benin to reaffirm counter-terrorism cooperation.

During the failed coup, Tigri reportedly denounced French involvement and invoked anti-imperialist rhetoric, ending a speech with the slogan “The Republic or Death” — a phrase now associated with Burkina Faso’s military rulers. This language suggests ideological inspiration drawn from neighbouring junta-led regimes.

The Expanding Coup Zone

The events in Benin marked the third coup attempt in the Sahel region in 2025 — and the first to fail. Since 2020, Africa has recorded 17 coup attempts, 11 of which succeeded. The stretch of territory running across the Sahel and into West Africa has become the world’s most coup-prone region.

The Benin plot was swiftly condemned by the African Union, the European Union and Ecowas, yet celebrated by pro-Russian social media networks. This reaction highlights a growing divide between Russia-aligned military regimes in the Sahel and civilian governments that remain within the Ecowas framework.

Although Ecowas threatened force after Niger’s 2023 coup, Benin represents the first case where the bloc actually deployed troops to reverse an attempted takeover. Nigeria’s leadership appears determined to prevent further instability from moving southward — particularly given the threat posed by jihadist groups operating near its borders. Notably, on the same day the Benin coup unfolded, reports emerged that Nigeria was seeking additional French assistance to confront mounting insecurity.